My Co-Translation of Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives Published!

My Admiration for Archaeologists as Detectives

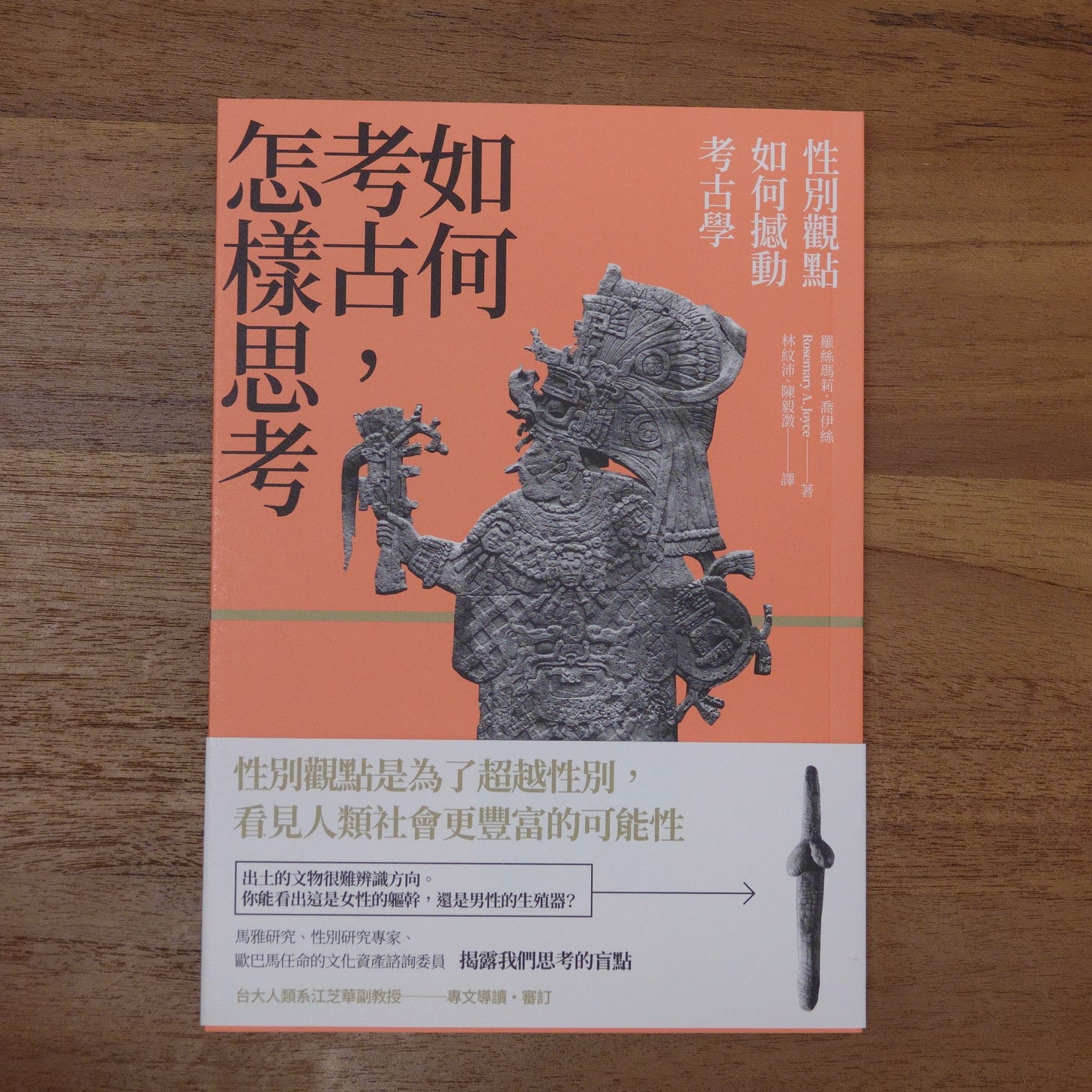

Happy holidays! In addition to The Dawn of Everything, another one of my translation projects was published this year: Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives: Sex, Gender, and Archaeology by Rosemary Joyce. I’m excited to share this co-translated book with you.

《翻譯鳥事一籮筐》是中英文雙語電子報。如果只想收到中文版,請到網站右上角的「My Account」內進行操作。有任何問題都歡迎來信聯絡,請直接回覆這封 E-mail 或寫信到 transcreation@substack.com。再次感謝你的訂閱支持!

這篇文章的中文版在這裡。

After completing the translation of The Dawn of Everything last year, I immediately began working on another archaeological book: Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives: Sex, Gender, and Archaeology. Translating two archaeology-related books back-to-back has deepened my admiration for archaeologists, whose work demands not only keen observational skills but also a boundless imagination.

For example, scholards studying figurines from Dolní Věstonice (in present-day Czech Republic), dating between 28,000 and 22,000 BC, discovered fascinating details through the fingerprints left on the figurines. They found that “small pellets of clay with fingerprints are the evidence of the maker tearing off sections of this material [clay]. A fingerprint visible on one female figurine falls in the size range for a child between seven and fifteen years of age, who touched it before the clay was dry … the explosion of the figurine bodies is so common that researchers suggest that it was not a flaw, but a deliberate effect that the makers wanted to produce.” (pp. 10-11)

From the material of the figurine, the way it was crafted, the various traces left on it, and the location of its excavation, archaeologists uncover every possible piece of information the object holds. The passage quoted above aligns with our general understanding of archaeology, but the “magic” of archaeologists doesn’t stop there: the phosphate content in the soil can indicate where humans carried out activities, analysis of soil from a house yard can reveal locations where ancient people prepared corn or swept the floor, and the proportions of certain elements in human bones can be used to infer their diet (pp. 32-33). The Dawn of Everything mentions many fascinating archaeological findings without detailing how they were derived. In contrast, Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives offers ample explanations and context.

In addition to discussing techniques, Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives importantly offers a reflection on archaeological research from a gendered perspective. Influenced by the global women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, many female scholars in archaeology began to ask, “Where are the women in the past?” Early research often linked specific genders to particular artifacts (p. 24), but this approach proved too limiting. The two-sex/two-gender model merely reflects our outdated stereotypes:

If we begin by looking for differences between men and women often we will find ways to discriminate between these two groups. But maybe the prior assumption that what matters is a binary distiction between men and women obscures other, more important, ways in which ancient people themselves distinguished difference. (p. 49)

The author also highlights another misconception: it is commonly believed that “sex,” as defined biologically, must conform to a binary model and is objectively true; however, this is not the case (pp. 43–45). After dismantling various stereotypes about sex and gender, how can archaeology reconstruct the picture of ancient societies from limited artifacts? Since sex and gender do not follow a single narrative or adhere to a binary model, the approach to reconstruction must likewise resist reduction and naturalization.

From noblewomen in classical Maya society and fighters in Bronze Age Northern Europe to midwives in nineteenth-century North America, each chapter of the book presents fresh and fascinating stories. However, the writing style—likely intended to be “academic”—makes the book somewhat challenging to read, requiring me to rearrange many sentences during the translation process. The following quote serves as a concluding remark. I believe the Chinese translation serves as an excellent bridge to present these academic achievements to Chinese readers.

Original:

Studies of women’s lives in societies with high degrees of difference in social rank make more sense if the women involved are not automatically treated as representative of a single categorical group united with all other women. (p. 77)

My translation:

研究女性的生活時,如果社會階級落差極大,我們就不應該不假思索地認為女性只有單一類別、身為研究對象的女性可以代表女性全體;需要擺脫這種想法,才能得到比較合理的研究成果。(頁 113)