From Snail to Stone

"The Everlasting Bloom" last year, "Lumière" this year, and an analogy for translation.

Happy Lunar New Year to everyone! It is my pleasure to officially launch Landscape of Transcreation at the beginning of the new year, and special thanks go to A Broad and Ample Road for their kind shout out. This newsletter has been started inspired by all their beautiful work.

Thank you readers and friends. Your subscription and support are genuinely appreciated. Every subscription is a heartwarming encouragement. I hope this small writing project will be a joy of reading in your life :)

In this issue, I talk about Water of Immortality currently on exhibition in MoNTUE, reflect briefly on “The Everlasting Bloom” last year, and come up with an analogy for translation. Thanks for reading. Any feedback is welcome.

Both the English and the Chinese versions of the newsletter will be updated every other Wednesdays. Please share with your friends!

《翻譯寫作的文字風景》是中英文雙語電子報。如果只想收到中文版,請到網站右上角的「My Account」內進行操作,也可以直接回覆這封E-mail或寫信到transcreation@substack.com,由我幫忙更改設定。再次感謝你的訂閱支持!

這篇文章的中文版在這裡。

At a corner of the exhibition hall stood “Sis,” bathed in the sunlight coming through the high floor-to-ceiling windows, her eyes half closed and her expression soft. This is my favorite corner where I linger most whenever I visit the Museum of National Taipei University of Education (MoNTUE). The statue, though made of marble, imparted a sense of warmth and softness, which I marveled at every time I circled around the work.

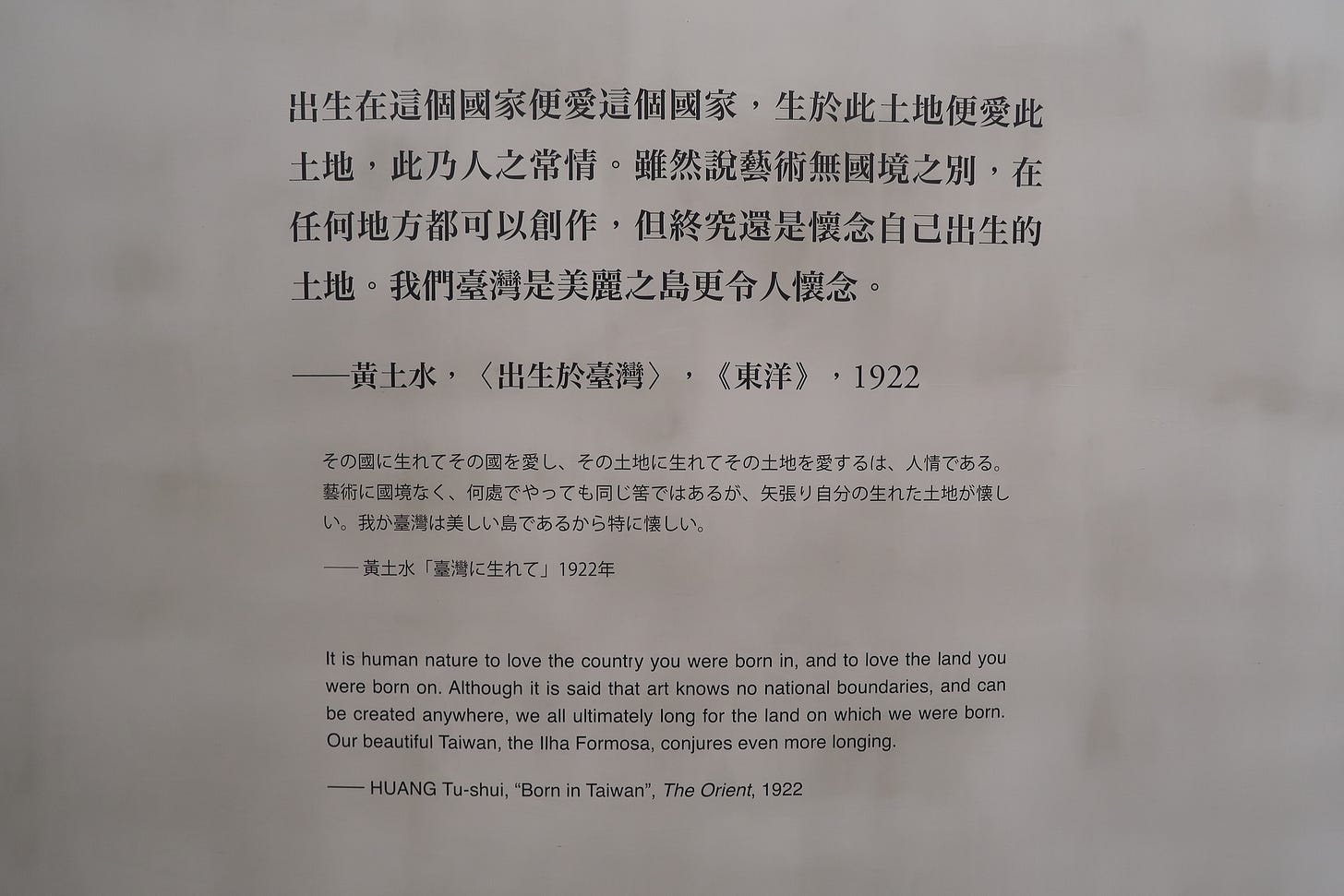

The official name of “Sis” is Water of Immortality (甘露水, Kam-lōo-tsuí), for which the sculptor Huang Tu-shui (黃土水, N̂g Thôo-tsuí, 1895-1930) was selected for Japan’s Imperial Art Exhibition for the second time. The year of 1921 in which Water of Immortality was selected coincided with the establishment of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會). In this light, it seems appropriate that this exhibition “Lumière” in memory of the centenary of the Taiwan Cultural Association chooses Water of Immortality as its central piece. The light of the Taiwan Cultural Association, however, probably does not shine straight on us a century away, as reflected by the decades of adversity suffered by Water of Immortality.

Huang Tu-shui, the sculptor of Water of Immortality, was born in Bangka (艋舺, today’s 萬華 Wanhua in Taipei) in 1895 to a poor family. His father worked as a rickshaw repair man, and his elder brother died young. After his father passed away, the 12-year-old child moved with his mother to Twatutia (大稻埕), where his second elder brother took care of them, and Huang went to the Daitotei Native School (大稻埕公學校, today’s Taipei Municipal Taiping Elementary School 台北市大同區太平國小). Like his father, Huang’s brother earned a living by repairing rickshaws, which relied much on woodworking skills. Influenced by his family, Huang also developed an interest in woodworking. In addition, Bangka and Twatutia where he grew up were teeming with temples and craftsman shops, and Huang was often found fascinated by masters working on Buddha statues. His love for sculpture probably found its roots there.

After graduated from the Daitotei Native School, Huang went to the National Language School (國語学校), an institute with teacher cultivation as its primary goal, which could be said to be “the top education institute” available for the Taiwanese at that time. While in the National Language School, Huang showed great talent for sculpture, and after his graduation was recommended by the Japanese colonial government to study in the Tokyo Fine Arts School (東京美術学校, today’s Tokyo University of the Arts 東京藝術大学) in 1915, where he became the first Taiwanese student. He lived in the dormitory Takasago Ryo (高砂寮)1 with other Taiwanese students in Tokyo. Reserved and quiet as he was, what was he thinking about when listening to the dormmates debating about the politics in Taiwan? Whatever his thoughts might be, he certainly nurtured a quiet love for his hometown, as was evident in the 1922 article “Born in Taiwan” and his last work in life, Water Buffaloes.2

In 1920, Huang was selected for Japan’s Imperial Art Exhibition with Mountain Child Playing Flute (山童吹笛), which made him the first Taiwanese ever selected. The Imperial Art Exhibition was the most important official art exhibition in Japan and could be said to embody the most authoritative say about art. Huang’s being selected was big news at that time, which must have uplifted the Taiwanese aspiring artists. In 1921, Huang was selected again with Water of Immortality, and he was selected for the Imperial Art Exhibition in total for four consecutive editions. Unfortunately, it was only a short period of 10 years from his rising to fame to his sudden passing away of illness. Since his death, there were many years before we saw succeeding sculptors like Chen Hsia-yu (陳夏雨, 1915-2000) and Yang Yuyu (also known as Yang Ying-feng 楊英風, 1926-1997). The gap for sculpture was perhaps wider than that for paintings.

After Huang’s death, his widow Liao Chiu-gui (廖秋桂) shipped Water of Immortality back to Taiwan in 1931. It was said that the work was originally on display in the lobby of the Taiwan Education Association (台灣教育會館), which served as the Taiwan Provincial Consultative Council (台灣省參議會) after the WWII. The authorities thought the female nudity statue immoral and intended to discard it, and a council member who learned of the news took it away to keep it in safety.3 Water of Immortality vanished from the public’s sight ever since.

It was a wonderful surprise that Water of Immortality missing for about half a century should one day reappear before the public. A year before, also a work of Huang Tu-shui bathed in sunlight at the same place, the bust of Girl might have elicited the reappearance of Water of Immortality in some destined way.

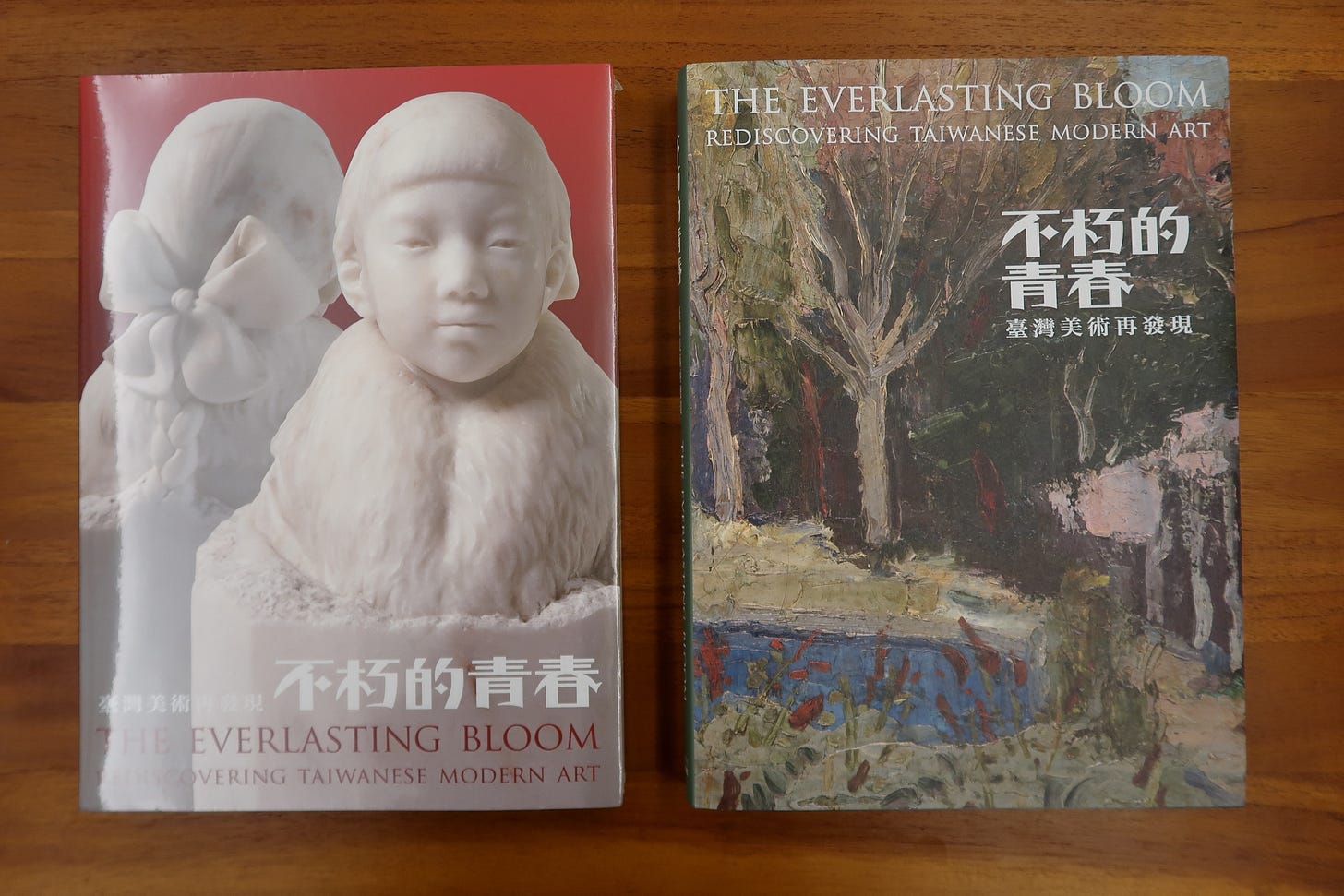

The bust of Girl, originally housed in Huang’s alma mater, Taiping Elementary School (the then Daitotei Native School), underwent restoration in 2020 and was exhibited in MoNTUE as one of the highlights of “The Everlasting Bloom” (exhibition date: October 17, 2020 to January 17, 2021). It was the first exhibition in which I saw so many works of Taiwanese modern artists on display at the same venue. The works belonged to many different collectors; tracing the whereabouts of the works was itself challenging enough, let alone borrowing them for the exhibition.4 Thanks to Dr. Lin Mun-lee (林曼麗) and her team for all their efforts, which made possible the grandeur of “The Everlasting Bloom” last year.

When I visited the exhibition with my friends last year, we were honored to have a friend familiar with the Taiwanese art history guide us through the gallery. I was impressed by her profound knowledge and learned a lot more about the era. What interested me most was the still life paintings: I had not realized a still life could depict daily objects dear and familiar to the artists, and that such objects could symbolize the deep attachment of the artists. The subjects of a still life were not necessarily apples, baskets and bottles on a white table cloth; the red round table, cabbage, tofu and fish were familiar sights to me, and I could relate to the connection between the paintings and the land.

“The Everlasting Bloom” truly resonated with the public. I went to the exhibition twice, the audience growing larger each time. Near the end of the exhibition, people had to line up for some time before getting admitted into the hall. It was unexpected to see so many people touched by Taiwanese modern art and craving to learn more about the past of these islands. It was the fruit of many generations’ hard work to arouse the public interest in the arts bursting into bloom a century ago.5

Much less expected was that this exhibition led to the “unearthing” of the missing Water of Immortality.

After the Water of Immortality was moved to Taichung together with the Taiwan Provincial Council (台灣省議會) in the 1950s, the Council did not relish the idea of displaying it in the new hall and asked the moving company to dispose of it. The statue was then placed outside the Taichung Railway Station, subjected to wanton defacement as it stood unprotected. Seeing this, Dr. Chang Hong-biao (張鴻標醫師) felt the statue deserved better respect, and thus housed it in the first floor of his clinic, where it stood for 16 years from 1958 to 1974. In the 1970s, with the society overshadowed by White Terror, people’s lives infiltrated by fear, Dr. Chang was afraid that he could not keep the statue safe from harm any more. As a result, he decided to hide Water of Immortality for the time being, which turned out to be a long while of 47 years.

All these years, the Chang family had been waiting for the time to return Water of Immortality to the country. Seeing the successful conclusion of “The Everlasting Bloom” last year, they thought probably the time had come. On December 17, 2021, Dr. Chang Shi-wen (張士文醫師), son of Dr. Chang Hong-biao, attended the opening ceremony of the exhibition, “Lumière: The Enlightenment and Self-Awakening of Taiwanese Culture,” and delivered a speech on behalf of his father and his family:

I am more fluent in Taiwanese, but today I will deliver the speech in Mandarin, for this day reminds me of my father’s words — “When the native Taiwanese (本省人) have learned to respect the mainlanders in Taiwan (外省人), and the mainlanders in Taiwan have also understood that they must respect the native Taiwanese, it is time to return Water of Immortality to the country.”

Isn’t today the right time?

Let us respect each other and rejoice together to welcome the dawn brought by the return of Water of Immortality.

It was probably in the year when I went to elementary school that “Sis” came to our house. She was very heavy, and several dozens of people put iron bars on the floor to move Sis into our dining room. Every day when I went home at noon after school, I put my school bag at her feet and gobbled down the food in spite of her silent gaze at me. Mom would then come in and tell us to start writing homework as soon as we finished the lunch, or Sis would be angry.

I did not know the name of Sis, until one day in the third grade of high school, I came across a report on Lion Art Monthly (雄獅美術) by chance. I was totally caught off-guard, not knowing how to react: the magazine said that her official name was Water of Immortality, and that her whereabouts remained unknown.

Father loved music and art. Whenever he had time, he would play with clay in the dining room before Water of Immortality. As a surgeon, he was skillful at immobilizing the fractures of patients with a cast. He dealt with the plaster by himself and enjoyed the work. Some suggested him make a replica out of Water of Immortality in his possession. Father replied that how humble and insignificant we were before Water of Immortality, and that he dared not commit sacrilege to the master (Huang Tu-shui).

In my college years, several of the seniors in the art world came to our house to confer with Father on the proper arrangement for Water of Immortality. They felt reassured and went away after learning Father’s plan.

Father emphasized that we should not donate Water of Immortality to the country but should return it with all humility. Today, looking at you with your immortal youth and elegant beauty, I know well that I cannot call you Sis any more. You are now the most precious cultural asset of Taiwan.

Farewell, Water of Immortality, Sis in our hearts forever.

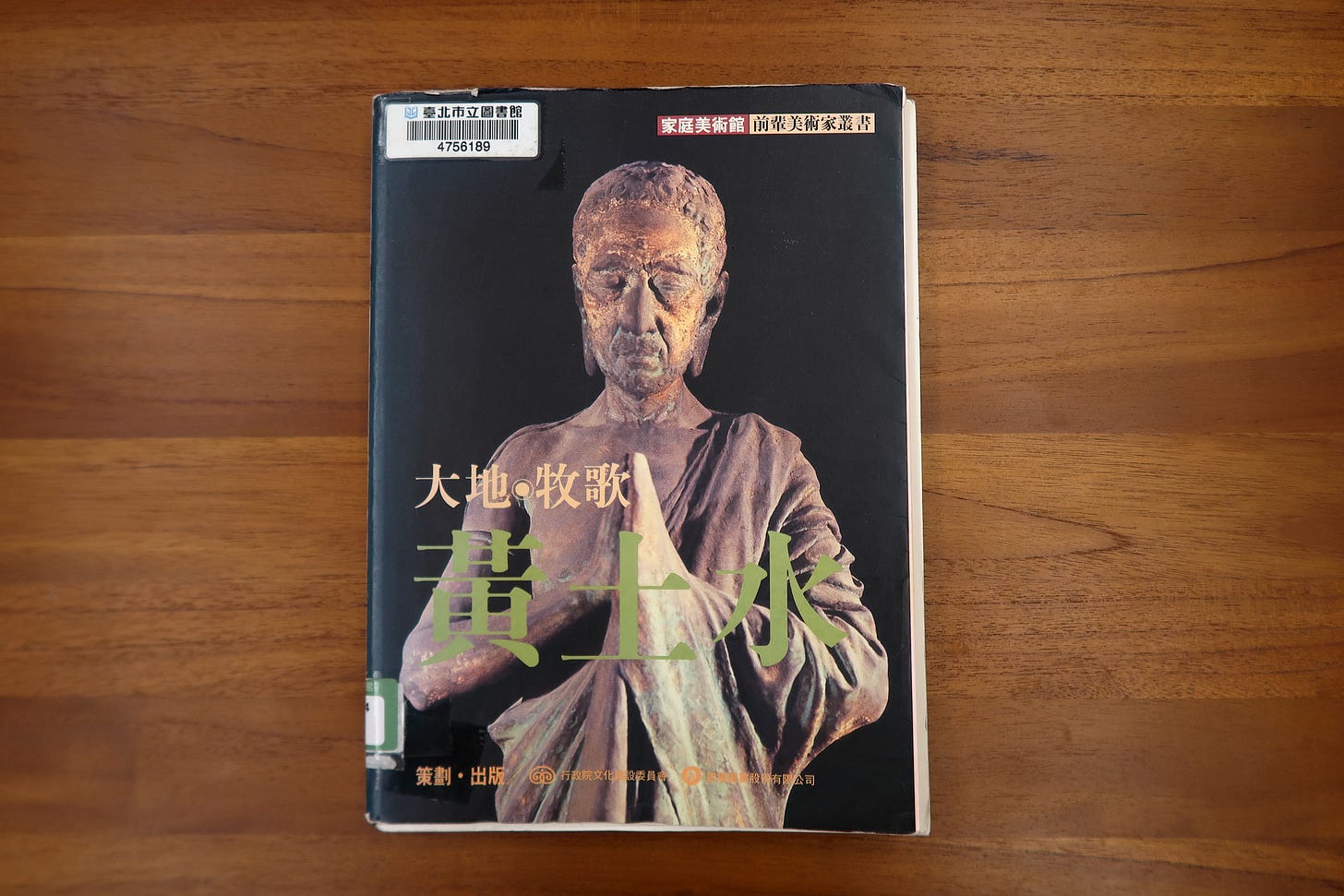

My own enlightenment to Taiwanese art history also owed much to the “Pioneering Artists Series” (前輩美術家叢書) of Lion Art (though not the magazines Dr. Chang read in his high school days). I remembered how distressed I was about the endless books to read and the numerous gaps to fill for my knowledge of Taiwanese history when I studied in the graduate school. Wondering from shelf to shelf in the library, I noticed the Lion Art “Pioneering Artists Series” comprising thin books with fluent and concise narratives. I borrowed almost as many books as I could carry from the shelf back to the research room and enjoyed the reading so much that I finished many books in just a few hours. It gave me a real sense of achievement in contrast to the daunting academic monographs I could barely finish. (Seeing my complacency, my classmate remarked calmly that such books were of course quick reading.) They were indeed a good series for all ages, introducing me to Taiwanese art history in a systematic way. Later on, I read a few papers, attended conferences and even wrote a term paper about Kinichiro Ishikawa (石川欽一郎, 1871-1945).

Reflecting on my journey into Taiwanese modern art, however, probably my earliest chance to study about such pioneering artists as Huang Tu-shui and Chen Cheng-po (1895-1947) was brought by an assignment in high school fine art class. The teacher asked us to design an exhibition pamphlet for a Taiwanese artist. I remembered I picked Li Shih-chiao (1908-1995) and went to Li Shih-chiao Museum of Art together with a classmate. What we saw in the museum escaped my memory, and my only remembrance of the museum was its location in a commercial building, quite at odds with my image of “museums.” And I remembered that another classmate who introduced Huang Tu-shui happened to feature Water of Immortality on the cover of her pamphlet. I went to the exhibition “Lumière” together with these two classmates, and we bumped into our high school geography teacher at the exhibition hall — what a lovely coincidence.

Having immersed in the artworks of the second floor, I walked up to the third floor and was surprised to find the painting I chose for my pamphlet cover years ago: Market Entrance by Li Shih-chiao. It was an oil on canvas almost as tall as I, in which the light and the line of sight converged on the lady in the center naturally, and the color of the original seemed to shine brighter than in my memory. The day was made merrier by the chance encounter with an old friend and a long-acquainted painting. I was grateful that the sense of awe and wonder inspired by the artworks could be continued from “The Everlasting Bloom” last year to “Lumière” this year, and it was touching to see Water of Immortality emerge from non-recognition and concealment to celebration and enshrinement.

Reading to this point, you may wonder what this article has to do with snails. In fact, snails have long been my analogy for translation. I always think my pace of translating too slow, as sluggish as a snail, and yet the most satisfactory part is to see the fruit of work produced by translation, like the trace left by a snail crawling over the ground. It sounds funny and not poetic at all.

Later on, as I thought about Water of Immortality and Girl, about the motivation of creation of the artists, about the things they intended to leave to the future generations by their gravers and brushes, it suddenly came to me that probably sculpture could serve as an analogy for translation too. Only that my work does not start from nothing; the experience is probably closer to looking at the original and carving it out in imitation with wood or stone (with some original texts, however, it seems I have to retrieve the flower from the fog). Now I come to think of it, languages and sculpture indeed share many metaphoric expressions: both can be polished, both can be refined. Yet since these expressions are conventional, the analogy between language, translation and sculpture may be a bit of a cliché? Then perhaps a snail sounds more special, and sort of adorable.

Be it snail or stone, both need the support of the land to prosper. With the feet firmly on the ground, we may better our work, leave our footprints, and bloom to the fullest. Continuing from “The Everlasting Bloom” last year, let us welcome the “Lumière” this year shone to us from the Taiwanese artists a century ago.

Exhibition Info of “Lumière: The Enlightenment and Self-Awakening of Taiwanese Culture”

Date: December 18, 2021 to April 24, 2022

Venue: MoNTUE, Museum of National Taipei University of Education

(No. 134, Sec. 2, Heping E. Road, Da’an District, Taipei City, Tawian 106)

Opening Hours: Tuesday to Sunday 10:00 to 18:00 (Closed on Mondays and National Holidays)

Book through https://reurl.cc/EZdLXR.

References

Li Chin-hsien 李欽賢, Dadi, Muge, Huang Tu-shui 大地‧牧歌‧黃土水 [Earth, idyll, and Huang Tu-shui]. Taipei: Xiongshi tushu, 1996.

Chien Hsiu-chih 簡秀枝, “Dui de ren, dui de shiju” 對的人, 對的時局 [the right people, in the right place, at the right time], ARTouch, October 22, 2021, https://artouch.com/views/interview/content-51264.html.

Wang Bao-er 王寶兒, “Jiazu shouhu ganlushui jin 50 nian, yishi: jie jie zaihui le” 家族守護「甘露水」近50年 醫師:姊姊再會了 [the family has protected Water of Immortality for almost 50 years; goodbye, sis, said the doctor], Central News Agency, December 19, 2021, https://www.cna.com.tw/news/acul/202112190151.aspx.

Ministry of Culture, “Taiwanese doctor shares personal story behind the iconic long-lost sculpture Water of Immortality,” December 20, 2021, https://www.moc.gov.tw/en/information_196_142081.html.

Takasago (高砂) is another Japanese term for Taiwan, so the name of the dormitory itself suggests that it is place for Taiwanese students.

The work Water Buffaloes is embedded on the wall of the central staircase between the second and the third floors in Taipei Zhongshan Hall. There are another two castings housed in the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts.

Li Chin-hsien 李欽賢 , Dadi, Muge, Huang Tu-shui 大地‧牧歌‧黃土水 [Earth, idyll, and Huang Tu-shui] (Taipei: Xiongshi tushu, 1996), 152. Li’s version of the story was slightly different from our later understanding, and the difference might arise from the uncertain whereabouts of Water of Immortality at that time.

These two videos offer brilliant introduction to the team’s work:

Pursuing the Everlasting Bloom

Exploring the Unfinished Landscape

“The Everlasting Bloom” exhibition attracted 45,000 visits, and the sale of the catalogue amounted to over 8,000 copies, which were some examples of the wide public interest it aroused. See Chien Hsiu-chih 簡秀枝, “Dui de ren, dui de shiju” 對的人, 對的時局 [the right people, in the right place, at the right time], ARTouch, October 22, 2021, https://artouch.com/views/interview/content-51264.html.